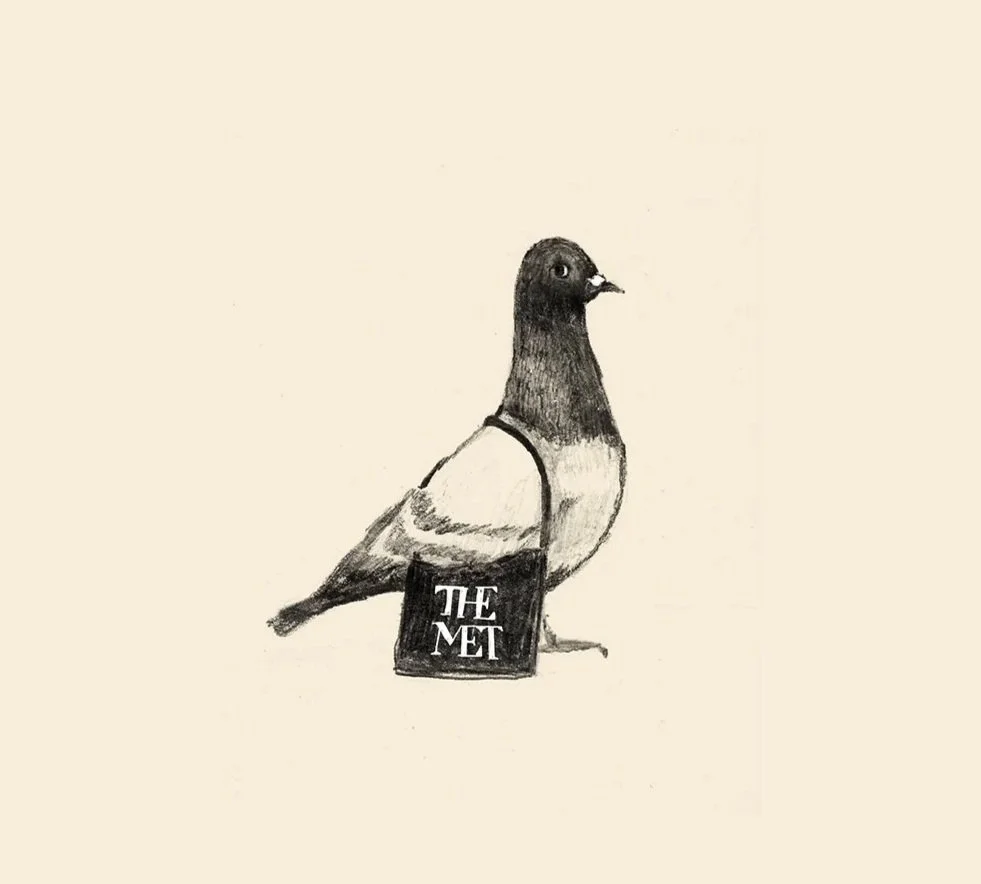

ARTE MIGAJERO.

La trampa del lenguaje

por Ale Tena

ARTE MIGAJERO.

La trampa del lenguaje

La cuerda de terciopelo: cómo el mundo del arte construyó su propia prisión

Carla se detiene frente a la entrada de una galería en la Roma CDMX, un sábado por la tarde. La puerta es de vidrio; puede ver las obras colgadas dentro, pero no hay ningún letrero con el horario, ni un timbre visible. Solo su reflejo mirándola de vuelta, atrapada entre las ganas de entrar y el miedo de no pertenecer a ese lugar. Tiene 34 años, trabaja en tecnología, gana bien, le encanta el arte que ve en Instagram. Y sin embargo, está ahí, paralizada en la acera, derrotada por una puerta sin nombre.

Esto no es un accidente. Es parte del diseño.

El arte contemporáneo ha pasado buena parte del último siglo construyendo una arquitectura de exclusión tan sofisticada que incluso quienes quieren acercarse, que tienen el interés y los medios, se sienten fuera. No se trata de rejas ni de guardias, sino de algo mucho más sutil: un sistema que te hace dudar si mereces entrar en primer lugar.

El círculo mágico que nunca se abre

Intenta entrar a una galería de alto nivel en CDMX, Nueva York o Madrid y comprar algo. En realidad, mejor ni lo intentes: no podrás, al menos no si eres “nadie”. Las galerías que dominan el mercado no venden por orden de llegada ni al mejor postor. Practican lo que llaman “colocación estratégica”: eligen cuidadosamente a quién le venden, decidiendo qué coleccionistas son lo suficientemente “serios” y dónde creen que la obra tendrá más impacto. Hay listas de espera de dos años. Las exposiciones se agotan un mes antes de abrir. La cuerda de terciopelo no está solo en la puerta: envuelve toda la transacción.

Henrik Potter, artista y gestor de la Free Art Fair, lo resumió sin rodeos: no puedes simplemente entrar a una galería prestigiosa y comprar una pieza. Te dirán que la exposición se agotó antes de inaugurarse y que hay una lista de espera interminable. Los galeristas llaman a esto “proteger la biografía de la obra”, asegurarse de que termine en las manos correctas. Los demás lo llamamos por su nombre: elitismo. Un filtro que garantiza que solo ciertas personas —con las credenciales, contactos o apellidos adecuados— tengan acceso.

Y no se trata solo de dinero. Muchos ricos también son rechazados. Las galerías vigilan de cerca el comportamiento de los compradores y pueden vetar a quienes especulan o simplemente ofrecerles obras de menor perfil si cometen alguna falta. En este sistema, conocer las reglas no escritas importa más que amar el arte.

La alianza académica: cómo las universidades se convirtieron en guardianes

Pero la exclusión no empieza en la puerta de la galería. Empieza mucho antes, en las universidades y programas de arte, donde durante décadas se ha decidido qué es “buen arte” y quién tiene derecho a hacerlo. Los curadores —y los supercuradores— son oráculos del presente: sus gustos determinan qué artistas entrarán en la historia y quiénes quedarán fuera. Si tu obra aparece en una muestra curada por alguien como Hans Ulrich Obrist, la visibilidad global llega al instante. Si no, es como si no existieras.

El problema no es que la especialización no importe, sino que esa especialización se ha vuelto dogma. El canon occidental se impuso como estándar y la obsesión con el contexto conceptual creó una jerarquía en la que conocer el código vale más que la emoción. Si no hablas el idioma —literal o simbólicamente— quedas fuera. Si no estudiaste con los profesores correctos, en las escuelas correctas, si no pasaste por las residencias adecuadas, estás intentando escalar el Everest en sandalias.

Los museos y galerías refuerzan este filtro. Al registrar la cultura visual del presente, también deciden qué será importante mañana. Pero ¿quién les otorgó ese poder de definir la memoria colectiva? ¿Y qué pasa con todas las artistas y creadores —mujeres, personas racializadas, voces del Sur Global— que no encajan en los criterios que Occidente sigue considerando “relevantes”?

La arquitectura del “tú no perteneces aquí”

Las barreras físicas son solo el principio, aunque siguen siendo reales. ¿Estos espacios deberían pensar en replantear el acceso? Quisiera pensar que si, para comenzar y a bote pronto se necesita vislumbrar cuatro dimensiones: cultural, social, económica y física. Incluso cuando aseguran querer abrirse a todos, sus edificios cuentan otra historia: pasillos imposibles para sillas de ruedas, cédulas de texto demasiado altas, tarifas de entrada que, aunque haya días gratuitos, siguen excluyendo a muchas familias.

El Museo Speed, por ejemplo, descubrió que cuando ofreció entrada libre los domingos, la asistencia de públicos diversos aumentó un 46% respecto a una exposición de pago.

Pero lo más profundo son las barreras sociales. Los visitantes de los museos no reflejan la diversidad real de sus comunidades. No es solo el precio: es la incomodidad. Es no tener con quién ir. Es entrar a una galería silenciosa y sentir todas las miradas encima, evaluando si eres del “tipo correcto”. Es el guardia que te sigue demasiado cerca o el guía que asume que quieres el recorrido infantil.

Algunos museos comienzan a reconocer esto. El propio Speed Museum se ha propuesto crear espacios verdaderamente acogedores, invitando de manera más amplia y repensando cómo se da la bienvenida. Pero reconocer el problema es apenas el primer paso. La verdadera pregunta es si las instituciones están dispuestas a desmontar las estructuras que les dieron poder.

La trampa del lenguaje

Luego está la forma en que hablamos del arte. Muchos comunicados de prensa parecen escritos por un comité de filósofos y publicistas: “La obra interroga el espacio liminal entre representación y abstracción, desestabilizando narrativas hegemónicas a través de procesos deconstructivos”. ¿Qué significa eso? Y más aún, ¿para quién está escrito?

El exceso de jerga convierte la experiencia artística en un código cerrado. No se trata de simplificar ni de “bajar el nivel”, sino de recordar que comprender no debería requerir un anillo descifrador. Los mejores críticos siempre han sabido explicar lo complejo con claridad; los peores se esconden detrás de las palabras.

Y seamos francos: a veces el emperador está desnudo. A veces una obra no es buena, o no está terminada, o simplemente es confusa, incluso para quien sabe de arte. Pero en este ecosistema, admitirlo te marca como inculto. Así que la gente asiente en silencio, fingiendo entender, y el ciclo de exclusión continúa.

La prisión del artista

El sistema no solo excluye al público: también asfixia a los artistas. Muchos quedan atrapados entre curadores y coleccionistas, condicionados por lo que el mercado aprueba. Temen experimentar, fracasar o desviarse. Corren de feria en feria, produciendo obras portátiles, fotografiables, perfectas para Instagram.

Los artistas jóvenes enfrentan un dilema imposible: crear lo que vende o crear lo que importa. Los afortunados logran ambas cosas; la mayoría no. Y porque galerías y museos se necesitan mutuamente —los museos dependen de las galerías para financiarse, las galerías dependen de los museos para legitimar su discurso— el sistema se convierte en un círculo vicioso donde todos señalan a otro como el obstáculo para el cambio.

Después de las protestas por justicia racial en 2020, muchas galerías prometieron diversificar sus listas. Pero un análisis reveló que el 57% de los nuevos artistas representados seguían siendo blancos. En Europa, las cifras son aún peores: solo el 28% eran personas no blancas, y además, se incorporaron más hombres que mujeres. Las puertas se abrieron apenas una rendija… y pronto volvieron a cerrarse.

Las consecuencias de las que no se habla

¿Qué nos cuesta toda esta exclusión? Nos cuesta arte. Nos cuesta voces. Nos roba la posibilidad de entrar a una galería y ver algo que nos conmueva porque fue creado por alguien que comparte nuestras preguntas o nuestra manera de mirar el mundo.

También nos cuesta bienestar. Hay estudios que muestran que el contacto frecuente con el arte mejora la salud mental, reduce la ansiedad y ayuda a procesar emociones cuando las palabras no alcanzan. Pero si el mensaje del mundo del arte es “aquí no perteneces”, millones de personas que podrían beneficiarse nunca cruzarán la puerta.

Y también lo pagan los artistas. ¿Cuántos talentos se quedaron en el camino por no pasar el filtro del posgrado? ¿Cuántos escultores abandonaron tras el quinto rechazo de una galería? ¿Cuántos fotógrafos decidieron que no valía la pena crear solo para complacer a curadores y coleccionistas? Nunca lo sabremos. Ese es el punto.

Grietas en los muros

Aun así, algo está cambiando. Algunos museos, como el Speed Art Museum, están repensando lo que significa “celebrar el arte”: pasar de un modelo de invitación unilateral a uno de colaboración y experiencia compartida. Entienden que la diversidad no es una moda, sino una cuestión de supervivencia.

El verdadero acceso empieza cuando las comunidades —personas con discapacidad, grupos raciales, minorías culturales— participan desde el diseño de los programas, bajo el principio de “nada sobre nosotros sin nosotros”. No se puede crear inclusión desde un comité si ese comité no incluye a quienes se pretende invitar.

Las redes sociales también han abierto grietas en el sistema. Hoy los artistas pueden construir audiencias sin pedir permiso a una galería, y los coleccionistas pueden descubrirlos fuera del circuito oficial. Claro, esto trae sus propias presiones: algoritmos en lugar de curadores. Pero al menos ha cambiado la conversación.

La pregunta que deberíamos hacernos

Carla sigue frente a la galería. Busca el nombre en su teléfono. Descubre que sí está abierta, que acepta visitantes, que solo tiene que tocar un timbre invisible. Lo hace. La dejan pasar.

Adentro, la galerista es amable. Explica las obras, menciona precios que hacen que el salario de Carla parezca pequeño. Le entrega una postal, le agradece su visita. La exposición es interesante, de verdad lo es. Pero Carla sale sintiendo lo mismo que antes: que ese espacio no fue hecho para ella. Que fue tolerada, no bienvenida. Que apreciar el arte requiere credenciales que no posee.

El mundo del arte ha pasado tanto tiempo construyendo muros que olvidó cómo construir puentes. Su sistema de validación —las escuelas correctas, las galerías correctas, los coleccionistas correctos, los museos correctos— se ha vuelto un circuito cerrado, una conversación entre unos pocos miles mientras miles de millones quedan afuera, preguntándose qué se están perdiendo.

Y tal vez la pregunta que debería quitarle el sueño al arte contemporáneo sea esta: ¿y si la exclusividad está matando al arte mismo? ¿Y si tanta protección no está resguardando nada que valga la pena proteger?

Los museos pierden visitantes. Las galerías venden menos. Los artistas venden por Instagram. Los muros se derrumban no porque los rebeldes los tiren, sino porque ya no sirven a nadie: ni a las instituciones, ni a los artistas, ni al público.

La prisión que el mundo del arte construyó ya no mantiene a la gente fuera. La mantiene adentro. Y la cuestión no es si caerán los muros, sino si alguien notará cuando eso ocurra… o si el arte seguirá tan ocupado protegiendo su exclusividad que no verá el momento en que el resto del mundo dejó de interesarse.

Carla camina de regreso al metro. En el camino, abre Instagram y vuelve a mirar arte —donde las barreras son más bajas, las miradas menos severas y no tiene que preguntarse si es digna de observar. No es lo mismo que estar frente a la obra real. Pero al menos ahí nadie la hace sentirse pequeña por intentarlo.

Esa es la verdadera tragedia. No que el arte sea exclusivo, sino que nos haya enseñado a agradecer las migajas.

/

MIGAJERO(CRUMB) ART :

The Trap of Language

The Velvet Rope: How the Art World Built Its Own Prison

Carla stands before the glass door of a gallery in Mexico City’s Roma district, on a Saturday afternoon. Through the transparent pane she can see the works hanging inside, but there’s no sign with opening hours, no visible doorbell. Only her own reflection staring back—caught between the desire to enter and the fear of not belonging.

She’s thirty-four, works in tech, earns a decent living, and loves the art she scrolls through on Instagram. And yet here she is, frozen on the sidewalk, defeated by a nameless door.

This is no accident. It’s part of the design.

For much of the past century, contemporary art has been busy constructing a remarkably sophisticated architecture of exclusion—so refined that even those eager to approach it, those with curiosity and means, often feel locked out. These aren’t bars or guards; it’s something far subtler: a system that makes you question whether you even deserve to step inside.

The Magic Circle That Never Opens

Try walking into a high-end gallery in Mexico City, New York, or Madrid and buying something. Actually, don’t bother—you probably can’t, not unless you’re a “somebody.” The galleries that dominate the market don’t sell to the first person who walks in or to the highest bidder. They practice what they call strategic placement: carefully selecting who gets to buy, deciding which collectors are “serious enough” and where the work will have the greatest impact.

Waiting lists stretch for two years. Shows sell out a month before opening. The velvet rope isn’t just at the door—it wraps around the entire transaction.

Henrik Potter, artist and manager of the Free Art Fair, put it bluntly: you can’t simply walk into a prestigious gallery and buy a piece. You’ll be told the show sold out before it opened, and that there’s an endless waiting list. Gallerists call this protecting the work’s biography—making sure it lands in the right hands. The rest of us have another word for it: elitism.

It’s a filter ensuring that only certain people—with the right credentials, contacts, or last names—gain access. And it’s not just about money. Many wealthy people are turned away as well. Galleries closely monitor collectors’ behavior, and those who speculate, flip, or offend can be quietly blacklisted—or offered only lesser works. In this ecosystem, knowing the unwritten rules matters more than loving the art.

The Academic Alliance: How Universities Became Gatekeepers

But exclusion doesn’t begin at the gallery door. It starts much earlier—in art schools and academic programs that, for decades, have dictated what counts as “good art” and who has the right to make it.

Curators—and their more powerful counterparts, the super-curators—are the oracles of the present: their taste decides which artists will enter history and which will vanish. If your work appears in a show curated by someone like Hans Ulrich Obrist, you’re instantly visible to the world. If not, you might as well not exist.

The problem isn’t specialization itself, but how it hardened into dogma. The Western canon became the default standard, and the obsession with conceptual framing created a hierarchy where fluency in theory outweighed emotional resonance. If you don’t speak the language—literally or symbolically—you’re excluded. If you didn’t study under the right professors, at the right schools, or attend the right residencies, you’re climbing Everest in sandals.

Museums and galleries reinforce this filter. By documenting the visual culture of the present, they also decide what will matter tomorrow. But who gave them that power to define collective memory? And what happens to all the artists—women, racialized creators, voices from the Global South—who don’t fit the criteria Western institutions still call “relevant”?

The Architecture of You Don’t Belong Here

Physical barriers are just the beginning, though they remain real. Should these institutions reconsider what “access” means? Absolutely—and to start, one must recognize its four dimensions: cultural, social, economic, and physical.

Even when they claim to open their doors to everyone, their buildings tell another story: corridors impossible for wheelchairs, wall labels hung too high to read, entry fees that—even with free days—still exclude countless families.

The Speed Museum, for example, found that when it offered free admission on Sundays, attendance from diverse audiences rose by 46% compared to ticketed exhibitions.

But the deeper barriers are social. Museum visitors rarely reflect the diversity of their communities. It’s not just about price—it’s about discomfort. It’s about not having someone to go with. It’s walking into a silent gallery and feeling every gaze upon you, assessing whether you belong. It’s the guard who follows you too closely or the docent who assumes you want the “kids’ tour.”

Some museums are starting to confront this. The Speed Museum itself has pledged to create genuinely welcoming spaces, broadening invitations and rethinking how people are greeted. But acknowledgment is only the first step. The real question is whether institutions are willing to dismantle the very structures that gave them power.

The Trap of Language

Then there’s the way we talk about art. Many press releases read as if written by a committee of philosophers and PR agents:

“The work interrogates the liminal space between representation and abstraction, destabilizing hegemonic narratives through deconstructive processes.”

What does that even mean—and more importantly, who is it written for?

An excess of jargon turns the artistic experience into a locked code. The goal isn’t to “dumb things down,” but to remember that understanding shouldn’t require a cipher ring. The best critics have always made complexity clear; the worst hide behind their words.

And let’s be honest: sometimes the emperor has no clothes. Sometimes a work simply isn’t good, or it’s unfinished, or it’s confusing—even to those who “know” art. But in this ecosystem, admitting that marks you as uncultured. So people nod in silence, pretending to understand, and the cycle of exclusion continues.

The Artist’s Prison

The system doesn’t just exclude the public—it suffocates the artists too. Many find themselves trapped between curators and collectors, conditioned by what the market approves. They fear experimentation, failure, deviation. They rush from fair to fair, producing portable, photogenic works—perfect for Instagram.

Young artists face an impossible dilemma: make what sells or make what matters. The lucky few do both; most do neither. And because galleries and museums depend on each other—museums on galleries for funding, galleries on museums for legitimacy—the cycle becomes a closed loop where everyone blames someone else for the lack of change.

After the racial justice protests of 2020, many galleries pledged to diversify their rosters. But analysis showed that 57% of newly represented artists were still white. In Europe, the numbers were worse: only 28% were people of color, and more men than women were added. The doors opened a crack… and quickly closed again.

The Unspoken Cost of Exclusion

What does all this exclusion cost us? It costs us art. It costs us voices. It robs us of the chance to walk into a gallery and be moved by something created by someone who shares our questions, our way of seeing the world.

It also costs us well-being. Studies show that regular exposure to art improves mental health, reduces anxiety, and helps people process emotions when words fall short. But if the message the art world sends is “you don’t belong here,” millions who could benefit from that contact will never cross the threshold.

And artists pay the price, too. How many talents were lost because they couldn’t afford a graduate program? How many sculptors gave up after their fifth gallery rejection? How many photographers decided it wasn’t worth creating just to please curators and collectors? We’ll never know—and that’s precisely the tragedy.

Cracks in the Walls

And yet, something is shifting. Some museums, like the Speed Art Museum, are reimagining what it means to “celebrate art”: moving from a one-way invitation to a collaborative, shared experience. They understand that diversity isn’t a trend—it’s survival.

True access begins when communities—people with disabilities, racial and cultural minorities—participate in the design of programs themselves, under the principle of nothing about us without us. Inclusion can’t be built by a committee that excludes the very people it aims to invite.

Social media has also cracked open the system. Artists can now build audiences without waiting for a gallery’s blessing, and collectors can discover them outside official circuits. Of course, that comes with new pressures—algorithms instead of curators—but at least the conversation has changed.

The Question We Should Be Asking

Carla is still standing at the gallery door. She looks up the name on her phone and finds out it is open, that visitors are welcome, that she only needs to press an invisible buzzer. She does. They let her in.

Inside, the gallerist is polite, even warm. She explains the works, mentions prices that make Carla’s salary feel small. She hands her a postcard, thanks her for coming. The exhibition is interesting—it really is. But Carla leaves feeling the same as before: that the space wasn’t made for her. That she was tolerated, not welcomed. That appreciating art requires credentials she doesn’t have.

The art world has spent so long building walls that it forgot how to build bridges. Its system of validation—the right schools, the right galleries, the right collectors, the right museums—has become a closed circuit, a conversation among a few thousand while billions remain outside, wondering what they’re missing.

And maybe the question that should keep contemporary art awake at night is this:

What if exclusivity is killing art itself?

What if all this protection isn’t preserving anything worth protecting?

Museums are losing visitors. Galleries sell less. Artists sell through Instagram. The walls aren’t being torn down by rebels—they’re crumbling because they no longer serve anyone: not the institutions, not the artists, not the public.

The prison the art world built no longer keeps people out. It keeps them in. And the real question is not if the walls will fall, but whether anyone will notice when they do—or if art will be too busy guarding its exclusivity to see that the rest of the world stopped caring.

Carla walks back toward the metro. On her way, she opens Instagram and scrolls through art again—where the barriers are lower, the gazes softer, and she doesn’t have to wonder if she’s worthy of looking.

It’s not the same as standing before the real thing.

But at least there, no one makes her feel small for trying.

That is the true tragedy.

Not that art is exclusive—

but that it has taught us to be grateful for crumbs.